We Have Become Dinosaurs

Horsens, Denmark2020

A film by Kenni Eilert & Katrine Pahuus

References

MacDougall, D. (1997). The visual in anthropology. Rethinking visual anthropology, 276-295.

MacDougall, D. (1998). Transcultural cinema: Princeton University Press.

Miller, G., & McCausland, J. (Writers). (1979). Mad Max. In B. Kennedy (Producer). Australia: American International Pictures

Collaborators:

︎︎︎ Det Gule Pakhus

︎︎︎ Katrine Pahuus

MacDougall, D. (1997). The visual in anthropology. Rethinking visual anthropology, 276-295.

MacDougall, D. (1998). Transcultural cinema: Princeton University Press.

Miller, G., & McCausland, J. (Writers). (1979). Mad Max. In B. Kennedy (Producer). Australia: American International Pictures

Collaborators:

︎︎︎ Det Gule Pakhus

︎︎︎ Katrine Pahuus

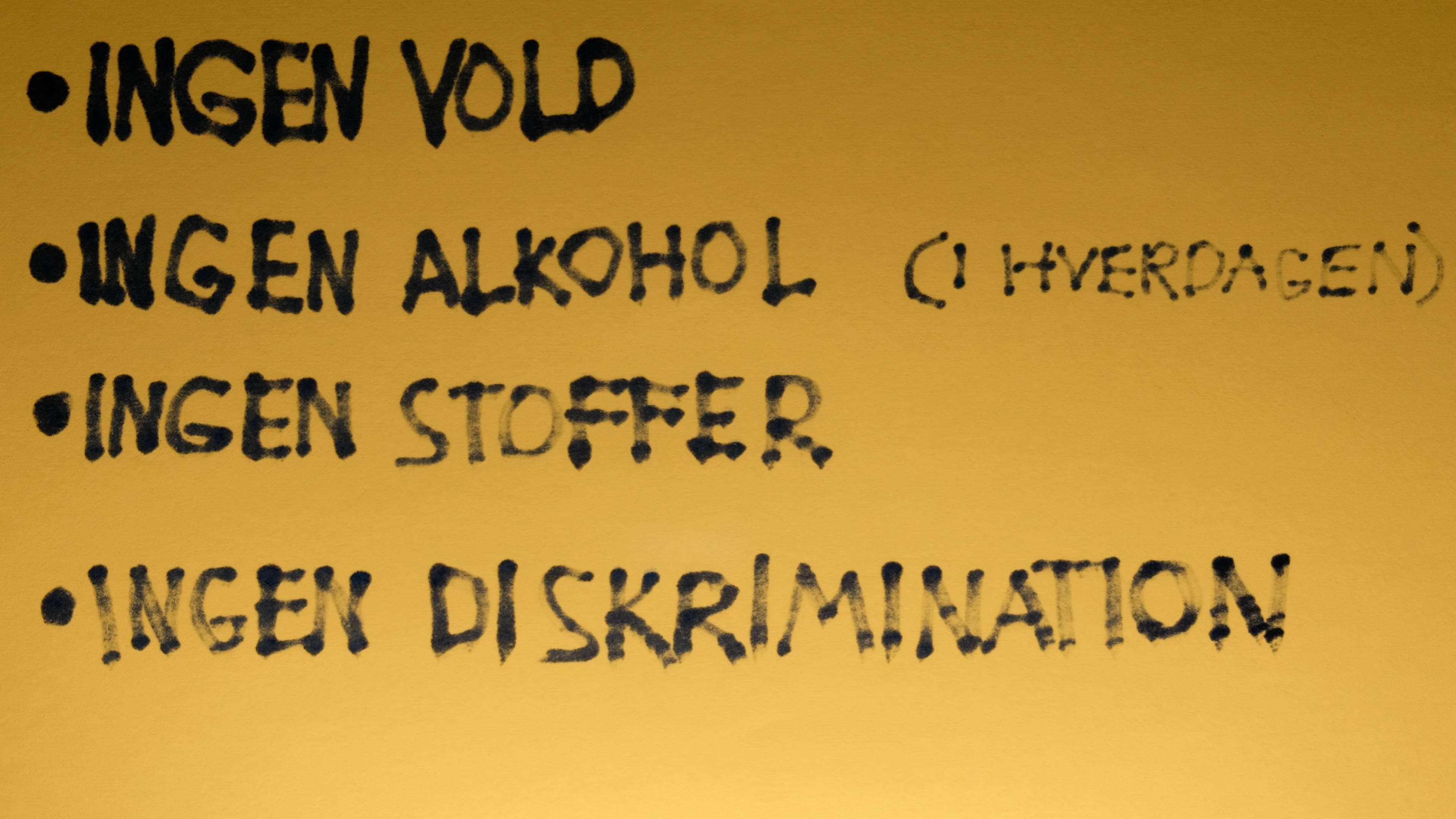

Det Gule Pakhus (DGP) has for the

last twenty-seven years acted as the centre for many of the maladapted and alternative

youths of Horsens. It has been the incubator and moral laboratory for countless

young people who sought creative and alternative forms of community across a

wide range of interests and talents. The main attractor has been rhythmic music

in various creative outbursts. The adjective maladapted needs to be

elaborated on in order for it not to come across as a derogatory term. As emic

terms, Maladapted Youth and Misfit are considered as a highly

desirable traits among the members of DGP. They refer to a strong collective

feeling of alienation, brought on by the expectations from the surrounding

society. Narratives of being misplaced or displaced and misunderstood as an individual,

saturates the story of DGP and its band of misfits. Being maladapted or a

misfit is for many an integral part of the identity that sprouts from this

creative collective in Horsens. It is a sociocultural retreat for those who do

not feel that they fit in anywhere else and due to the provocative and

inquisitive nature of underground punk culture, many of the young people talk

of DGP as a freehaven where they can express themselves in ways, which are not

aligned with the expectations of the surrounding community i.e. Society writ

large.

I myself have spent the better part of my life engaged in the activities of DGP. In the early nineties, the municipality in Horsens arranged summer activities for kids from low-income households which did not have the finances to go on summer holidays. I was attending such a summer activity at the age of ten, in the summer of 1994, where we were going to learn how to paint graffiti! I was scared out of my mind when I first saw of the older boys with dreadlocks, tattoos and mohawks in different colours, but at the same time I was completely engulfed and enthralled by these extravagant bums who, too me, looked like characters from James McCausland and George Miller’s post-apocalyptic classic from 1979, Mad Max (1979). Much has changed in the last 26 years but the narrative of the maladapted misfitstill take precedent when asking many of today’s members to explain how they found DGP and why they keep coming back.

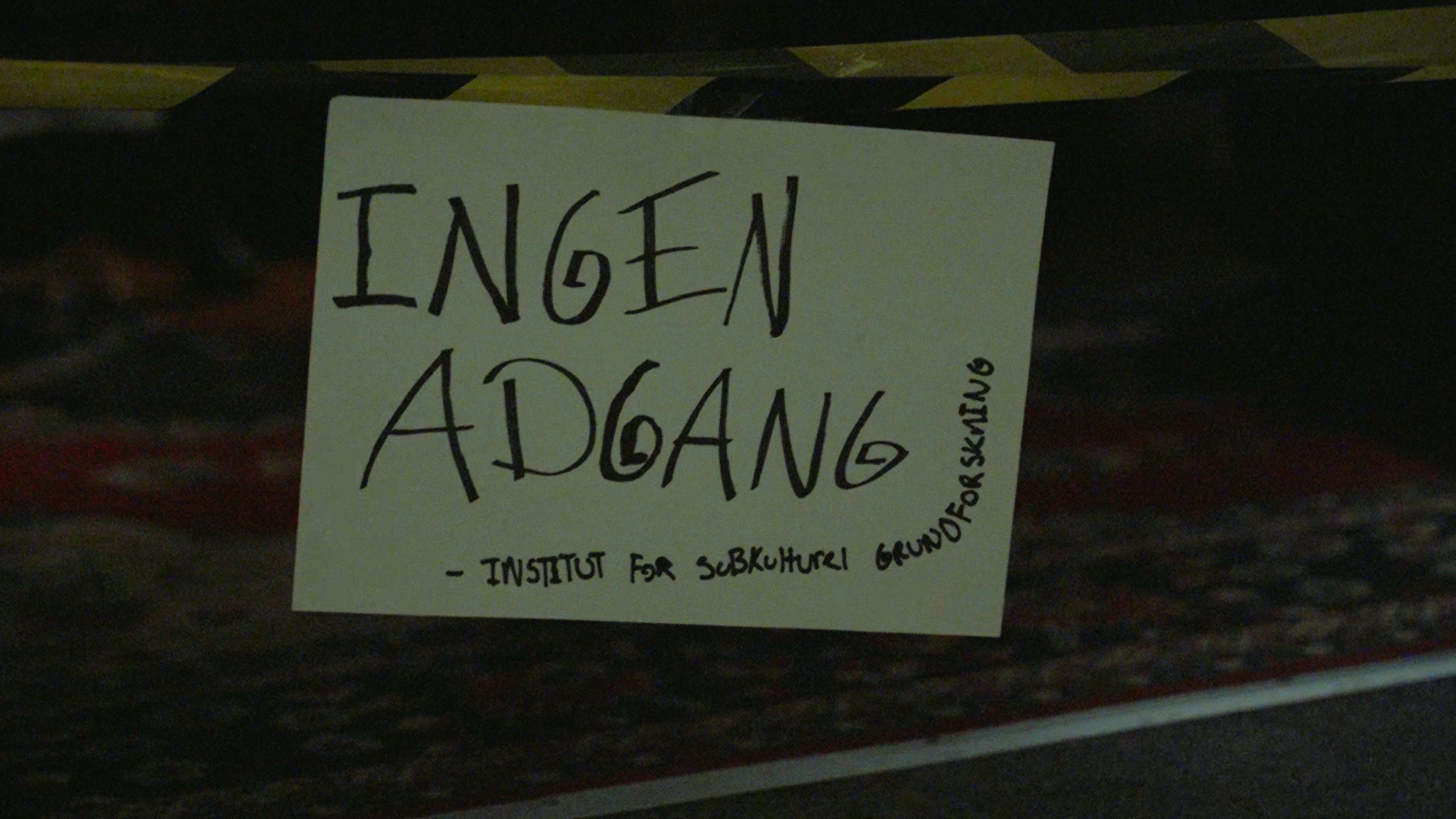

Initially We Have Become Dinosaurs was supposed to be a particularly framed conversation between myself and the curator of DGP, Simon, who is also an old friend of mine. My intention was to browse through a rather vast archive material I have gathered over the years and talk about old times. I wanted to re-enact and converse about all the things we have accomplished together and separately through the years, utilizing the archive footage as elicitation material to guide the discussion. The conversation never reached the archive material. I call Simon the curator at his own request, as he, in his own opinion, curates a piece of history that, in his words, "is slowly disappearing into oblivion in favour of development for purposes of development solely, in combination with neoliberal hypocrisy and cultural jealousy." His intentions with our conversation was to curate the most recent piece of the history. He wanted it to be recorded in order for it to become part of the archive material that I had brought to the occasion. On august 21st 2021 DGP will open the doors for the last time, after which the remaining members and the building will merge with the city’s commercial sound venue, KulisseLageret. WHBD is an attempt to accommodate the intentions put forth by my interlocutor, viz., to help frame the last chapter in the history of DGP. In the following I will elaborate on the collaborative aspects of WHBD.

Framing WHBD as Visual Anthropology

To elucidate some of the proficiencies of audio-visual representations and materials in anthropology, I will draw on David MacDougall’s (1997) description of visual ethnography. According to MacDougall, visual anthropology can serve as a metaphor for the real i.e. visual material in an ethnographic sense, holds the potential to act as a medium through which the observable real can be transported over vast distances and into the hands, eyes and minds of new spectators. Thus, becoming a visual representation of the experiences which, the anthropologist has encountered and recorded during fieldwork (ibid.:277). In this transition, MacDougall argues that there is an inherent vulnerability viz. that any uncaptioned photograph or audio-visual representation risks unforeseen interpretations manifesting unguided in the mind of the viewer (ibid.:289-290). This is something, we as anthropologists must recognize and implement in our work, in order to represent our interlocutors and ourselves in the best possible manner. Part of this recognition is to be found in one of the principal features of visual anthropology viz. the prospect of it serving as a means for our interlocutors to represent themselves through their own audio-visual productions, from which they can articulate their own views and positions. MacDougall conceptualizes this as Indigenous Media Production, a form of collaboration which engenders an emergence of new modes of dialogue between anthropologist and interlocutor (MacDougall, 1997, p. 283). Extending on this notion, in contemporary visual anthropology, collaboration and exchange between the interests of the anthropologist and those of our interlocutors are considered as an integral measure and fundamental principle for fieldwork and anthropological knowledge production. An important aspect of this is the fact that the power of exhibition no longer rests exclusively in the control of the anthropologist. As visual anthropology develops further, so does the responsibilities of the anthropologist because, according to MacDougall “[t]here is a moral imperative against allowing viewers to jump to the wrong conclusions.” (ibid.:290). We as anthropologists therefore have the responsibility of contextualising the visual material, in a way that does not allow for ill-informed interpretations. In a later article MacDougall (1998) argues that visual anthropology strongly influences the way we as anthropologists “regard cultural boundaries in the modern world including the most persistent one, between us and them” (ibid.:248, my emphasis). Audio-visual material allows the viewer or spectator to engage with the analytical arguments and the sentiments of both anthropologist and interlocutor in a more sensuously engaged manner than texts i.e. “visual anthropology opens more directly onto the sensorium than written texts and creates psychological and somatic forms of intersubjectivity between viewer and social actor.” (ibid.: 262).

In the context of this paper and the associated film, what I am arguing through MacDougall is, that my anthropological interest in DGP was intentionally instrumentalised by Simon through our collaboration, in such a way that I in effect was working as the curator’s assistant, as he was in the process of developing the framing of a future exhibition, thereby, momentarily annulling the cultural boundaries between anthropologist and interlocutor.

I myself have spent the better part of my life engaged in the activities of DGP. In the early nineties, the municipality in Horsens arranged summer activities for kids from low-income households which did not have the finances to go on summer holidays. I was attending such a summer activity at the age of ten, in the summer of 1994, where we were going to learn how to paint graffiti! I was scared out of my mind when I first saw of the older boys with dreadlocks, tattoos and mohawks in different colours, but at the same time I was completely engulfed and enthralled by these extravagant bums who, too me, looked like characters from James McCausland and George Miller’s post-apocalyptic classic from 1979, Mad Max (1979). Much has changed in the last 26 years but the narrative of the maladapted misfitstill take precedent when asking many of today’s members to explain how they found DGP and why they keep coming back.

Initially We Have Become Dinosaurs was supposed to be a particularly framed conversation between myself and the curator of DGP, Simon, who is also an old friend of mine. My intention was to browse through a rather vast archive material I have gathered over the years and talk about old times. I wanted to re-enact and converse about all the things we have accomplished together and separately through the years, utilizing the archive footage as elicitation material to guide the discussion. The conversation never reached the archive material. I call Simon the curator at his own request, as he, in his own opinion, curates a piece of history that, in his words, "is slowly disappearing into oblivion in favour of development for purposes of development solely, in combination with neoliberal hypocrisy and cultural jealousy." His intentions with our conversation was to curate the most recent piece of the history. He wanted it to be recorded in order for it to become part of the archive material that I had brought to the occasion. On august 21st 2021 DGP will open the doors for the last time, after which the remaining members and the building will merge with the city’s commercial sound venue, KulisseLageret. WHBD is an attempt to accommodate the intentions put forth by my interlocutor, viz., to help frame the last chapter in the history of DGP. In the following I will elaborate on the collaborative aspects of WHBD.

Framing WHBD as Visual Anthropology

To elucidate some of the proficiencies of audio-visual representations and materials in anthropology, I will draw on David MacDougall’s (1997) description of visual ethnography. According to MacDougall, visual anthropology can serve as a metaphor for the real i.e. visual material in an ethnographic sense, holds the potential to act as a medium through which the observable real can be transported over vast distances and into the hands, eyes and minds of new spectators. Thus, becoming a visual representation of the experiences which, the anthropologist has encountered and recorded during fieldwork (ibid.:277). In this transition, MacDougall argues that there is an inherent vulnerability viz. that any uncaptioned photograph or audio-visual representation risks unforeseen interpretations manifesting unguided in the mind of the viewer (ibid.:289-290). This is something, we as anthropologists must recognize and implement in our work, in order to represent our interlocutors and ourselves in the best possible manner. Part of this recognition is to be found in one of the principal features of visual anthropology viz. the prospect of it serving as a means for our interlocutors to represent themselves through their own audio-visual productions, from which they can articulate their own views and positions. MacDougall conceptualizes this as Indigenous Media Production, a form of collaboration which engenders an emergence of new modes of dialogue between anthropologist and interlocutor (MacDougall, 1997, p. 283). Extending on this notion, in contemporary visual anthropology, collaboration and exchange between the interests of the anthropologist and those of our interlocutors are considered as an integral measure and fundamental principle for fieldwork and anthropological knowledge production. An important aspect of this is the fact that the power of exhibition no longer rests exclusively in the control of the anthropologist. As visual anthropology develops further, so does the responsibilities of the anthropologist because, according to MacDougall “[t]here is a moral imperative against allowing viewers to jump to the wrong conclusions.” (ibid.:290). We as anthropologists therefore have the responsibility of contextualising the visual material, in a way that does not allow for ill-informed interpretations. In a later article MacDougall (1998) argues that visual anthropology strongly influences the way we as anthropologists “regard cultural boundaries in the modern world including the most persistent one, between us and them” (ibid.:248, my emphasis). Audio-visual material allows the viewer or spectator to engage with the analytical arguments and the sentiments of both anthropologist and interlocutor in a more sensuously engaged manner than texts i.e. “visual anthropology opens more directly onto the sensorium than written texts and creates psychological and somatic forms of intersubjectivity between viewer and social actor.” (ibid.: 262).

In the context of this paper and the associated film, what I am arguing through MacDougall is, that my anthropological interest in DGP was intentionally instrumentalised by Simon through our collaboration, in such a way that I in effect was working as the curator’s assistant, as he was in the process of developing the framing of a future exhibition, thereby, momentarily annulling the cultural boundaries between anthropologist and interlocutor.